The Deltic Sound That Lives Forever

There are moments in a railway enthusiast’s life that remain crystallised in memory, unchanged by the passage of decades. For those of us who witnessed the Deltic era, one such moment was standing on a platform as these magnificent machines prepared to depart. The anticipation would build first—a subtle tremor through the concrete beneath your feet, a change in the air itself that signalled something extraordinary was about to unfold.

Then came the distinctive rumble, growing into that unmistakable, powerful throb that seemed to resonate not just in your chest, but in your very soul. The smell of hot diesel mingling with platform smells, the shimmer of heat haze above the engine compartments, the way the platform itself seemed to vibrate with barely contained power. These weren’t merely locomotives. They were living, breathing entities with personalities forged in the workshops of English Electric, christened with names that honoured regiments and racehorses, destined to write their names into railway legend.

And then—acceleration. Not the gentle pulling away of lesser machines, but a purposeful, muscular surge announced by the eruption of blueish-grey exhaust smoke into the air. The roar of those twin Napier engines—two nine-cylinder opposed-piston units working in perfect harmony—created a symphony that railway enthusiasts would recognise instantly, even decades later. That sound. That unforgettable sound.

Preserving More Than Machines

Of the original fleet of twenty-two Class 55 Deltics that once thundered along the East Coast Main Line, only six survive today. Six, from twenty-two. It’s a sobering statistic that reminds us how close we came to losing this heritage entirely. Yet within that small number lies hope, dedication, and an unwavering commitment to keeping history not just preserved, but alive.

The Deltic Preservation Society maintains three of these survivors at their purpose-built facility at Barrow Hill Roundhouse, near Chesterfield in Derbyshire. But the DPS doesn’t preserve static exhibits behind velvet ropes. They maintain working locomotives—55009 ‘Alycidon’, 55015 ‘Tulyar’ (coming to the end of a very long restoration), and 55019 ‘Royal Highland Fusilier’—machines that still accelerate away from stations with that characteristic Deltic surge, still create that distinctive engine note that makes heads turn, still generate the excitement that transforms a railway platform into a theatre of memory.

This is preservation with purpose—the kind that lets a child today feel what we felt, hear what we heard, understand viscerally why these machines captured the imagination of a nation. The volunteers who arrive at Barrow Hill on cold winter mornings to maintain these machines aren’t just preserving locomotives. They’re preserving experience, sensation, connection. They’re ensuring that the sensory experience of a Deltic encounter—that unique combination of sound, vibration, smell, and sheer presence—remains part of Britain’s living railway heritage rather than fading into the sepia tones of nostalgia.

The Price of Keeping Dreams Alive

There’s a romance to preservation that often obscures its harsh realities. These aren’t vintage cars that can be garaged between summer rallies. They’re complex, demanding machines requiring constant attention, specialist knowledge, and rare parts that sometimes need to be manufactured from scratch, guided by fading blueprints and the memories of engineers who remember how things were done.

Modern safety standards, accessibility requirements, operational certifications—the regulatory burden alone would make a railway engineer from the 1960s weep. A single mainline certification can cost tens of thousands of pounds. Major overhauls run into six figures. Every time a Deltic turns a wheel on Britain’s railways, it represents thousands of volunteer hours and significant financial investment.

The work never stops. Preservation isn’t a restoration project with a completion date—it’s a commitment that stretches forward indefinitely, funded year after year through the dedication of supporters who refuse to let this heritage fall silent.

Standing Together

Memories of Motion was founded on a simple belief: that the stories captured in railway photography deserve to be preserved, celebrated, and shared. When we look at Trevor Ermel’s stunning image of 55018 ‘Ballymoss’ at York station—a locomotive that no longer survives, captured in a moment of operational glory—we see more than composition and light. We see a testament to an era, a connection to those who built and drove these machines, a bridge between then and now.

It seemed natural, then, to stand with the Deltic Preservation Society in their mission. Not through token gestures, but through genuine, meaningful support that helps keep those pistons moving, those generators turning, those magnificent machines thundering along Britain’s railways.

How We’re Supporting the DPS

The Collaboration Products

Class 55 Deltic 55018 ‘Ballymoss’ stands at York having arrived with the 12.05 1L42 London Kings Cross to York service on 3rd August, 1981. It would then work the 15.50 1A26 service back to London Kings Cross. A lone trainspotter looks on, no doubt soaking up the smell and noise from the Napier engines.

We’ve created four exclusive photographic products featuring Trevor Ermel’s image of 55018 ‘Ballymoss’ at York station. Fine-art prints and three different framed prints, each celebrating these legendary locomotives. When you choose one of these products, you’re not making a purchase—you’re making a statement. You’re saying that the smell of hot diesel matters, that the platform vibrations matter, that the next generation deserves to experience what we experienced.

One hundred per cent of profits from these collaboration products go directly to the Deltic Preservation Society to support their preservation work at Barrow Hill. Not a donation. Not a percentage. Everything.

You’re supporting the engineers and volunteers who arrive on cold winter mornings to maintain machines that British Rail declared surplus decades ago. You’re helping ensure that future generations won’t just read about Deltics in history books—they’ll stand on platforms and feel the world shift as 3,300-horsepower machines demonstrate what British engineering achieved.

You can buy one of these prints here and help support the DPS.

For Delic Preservation Society Members

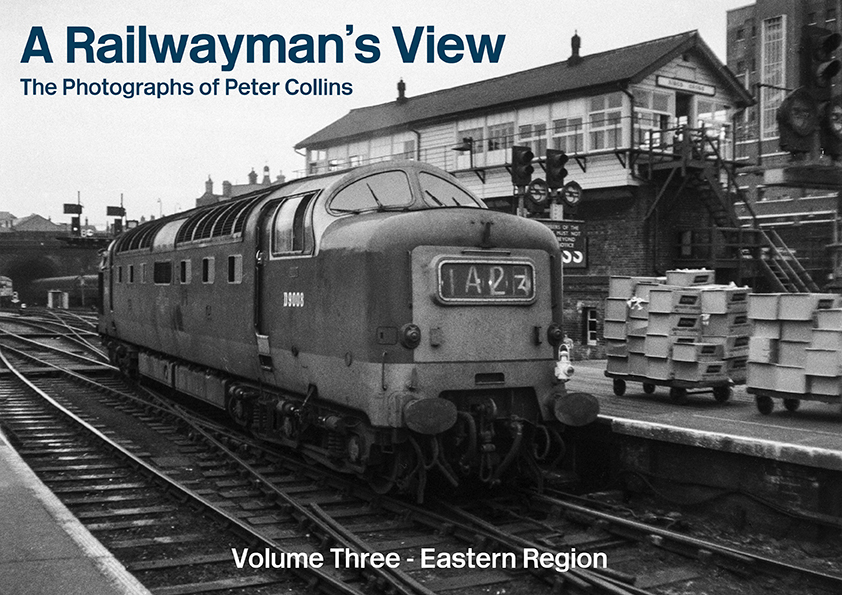

If you’re a current member of the Deltic Preservation Society, we recognise your existing commitment to keeping this heritage alive. Purchase Peter Collins’ Eastern Region volume from us and receive free delivery. Additionally, we’ll donate £5.00 directly to the Society with your order—our way of saying thank you for your ongoing support of operational preservation.

This isn’t marketing. It’s fellowship. It’s standing shoulder to shoulder with those who understand that some things are worth preserving, not because they’re profitable, but because they matter.

Come and Experience Living History

Words and photographs can only capture so much. To truly understand what we’re preserving, you need to experience it. Visit the Deltic Preservation Society at their Barrow Hill facility. See 55009 ‘Alycidon’, witness the ongoing restoration of 55015 ‘Tulyar’, stand beside 55019 ‘Royal Highland Fusilier’. Better yet, catch them on heritage railways or occasional mainline tours—those rare, precious opportunities to feel that distinctive surge of acceleration, to hear that Napier symphony, to understand why we refuse to let this heritage fade.

The DPS website at www.thedps.co.uk provides details of opening times, operational calendar, and upcoming mainline tours. These aren’t just visits—they’re pilgrimages to a time when engineering ambition matched operational necessity, when drivers were custodians of proud traditions, when a locomotive wasn’t just a machine but a personality.

Your Part in the Story

The DPS shoulders this burden with grace and determination, but they cannot do it alone. Every supporter, every purchase, every contribution helps ensure that the sensory experience of a Deltic encounter remains part of Britain’s living railway heritage rather than fading into memory.

This is your chance to be part of the story. Not as a footnote, but as an active participant in keeping history alive and operational. Your support matters. Not in some abstract, charitable sense, but in the concrete reality of keeping these magnificent machines thundering along Britain’s railways.

Together, we’re preserving more than locomotives. We’re preserving the moments that transform casual observers into lifelong enthusiasts. We’re preserving the sound that lives forever in the memories of those who’ve heard it. We’re preserving the visceral understanding that some achievements of British engineering deserve to remain not merely documented, but experienced.

This is heritage preservation that you can see, hear, and feel.